Forget Bernie Madoff, forget Enron, forget WorldCom. Forget all the Wall Street banks circa 2008. That's micro-potatoes fraud compared to the potential massive macro fraud that could be lurking on the other side of the Pacific.

I'm speaking of China – the “eighth wonder” of the economic world whose unrelenting gross domestic product (GDP) growth has attracted trillions of dollars of foreign investment over the past two decades.

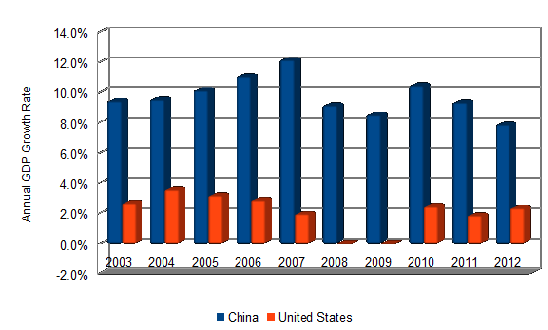

Contrasting China's annual GDP growth rates with that of the United States over the past decade, it's easy to see why so many investors are enthralled with China's prospects.

China and United States Annual GDP Growth

In 2011, the U.S. economy grew to $15.1 trillion from $10.9 trillion in 2003, while China's grew to $7.1 trillion from $1.6 trillion. Should the past remain prologue, the International Monetary Fund predicts China will soon overtake the United States as the world's number one economy.

At least a few analysts (and I'm one) have serious doubts that China's reported GDP growth rates reflect reality. For one, the numbers are generated by the government. In addition, GDP measures spending, not value created. The distinction matters, because China is likely creating much less value than the numbers indicate.

I say that because China is largely a centrally planned economy – one much more centrally planned than the United States. China's government directs a large percentage of spending that's reflected in its GDP numbers.

Central planners are hardly the best capital allocators. If money is spent on goods or services few people want, capital is wasted. GDP fails to capture that distinction.

Most of us are aware that China's central planners have committed immense amounts of capital to infrastructure – roads, bridges, housing, power plants, etc. These massive projects are easy to identify and imply economic progress, which is why bureaucrats love them.

Not surprisingly, more money continues to flow into infrastructure. China Development Bank increased lending to urbanization projects last year, in response to Beijing's directives to boost economic growth. Loans were directed to coal-oil transport, water conservation, agriculture, forestry, telecommunications, power networks and public infrastructure.

So is the money well-spent?

It's looking more doubtful. Data from the China Banking Regulatory Commission show non-performing loans (NPLs) are on the rise. NPLs among Chinese lenders have increased four consecutive quarters (through the third quarter of 2012) – the longest period of asset-quality deterioration since 2004.

What's more, the private sector appears to be bearing the cost of public works. A recent article at Minyanville.com offered an insightful quote to the plight of the non-bureaucrat:

“When there is only so much money to go around, bank branch officials will lend to the large, state-owned companies first and the others have to fight over what is left,” says David Chow, head of the principal investment group at Taiwanese bank CDIB and a former managing director at Beijing government-owned China Development.

China is also frequently lauded as an exporting powerhouse. Indeed, exports accounted for 31% of China's GDP in 2011.

But again, China's export model was developed under the supervision of central planners.

Many bureaucrats (and many economists for that matter) believe a sale outside the country is more meaningful than a sale within the county. This is mercantilism – the belief that a positive balance of trade (more money related to goods and services) is preferable to a negative balance of trade.

It's a false, discredited belief, but one China has paid a steep price for adhering to. If the cost of China’s export policy were properly accounted for, it would become evident that many of its exports that appear profitable in fact aren’t.

I say that because of the government's manipulation of its currency (sound familiar?). What the Chinese call export-driven growth is really a policy of holding the currency exchange rate below the market rate in order to reduce the domestic monetary costs of Chinese exports.

Just like in the United States, China's spending binge has been fueled by a rapid increase in the money supply. China's central bank announced last month that M2, a broad measure of money supply, grew by 13.8% year-over-year to 97.42 trillion yuan ($15.71 trillion) in 2012.

That figure is 1.5 times the total M2 in the US, which stood at $10.4 trillion in 2012, and 1.3 times that in the euro area.

Growth in China's Money Supply

Rapid expansion of the money supply nearly always leads to investment bubbles, which never burst benignly.

Now, combine monetary expansion with reports of the efficacy of China's central planner and the country's impending ascension to economic superpower, and an insightful quote from 18th–century economist Adam Smith comes to mind:

“When the profits of trade happen to be greater than ordinary, overtrading becomes a general error.” And rate of profit, Adam Smith said, “is always highest in the countries that are going fastest to ruin."

High profits are associated with high growth, and growth is a siren song to many investors. I won't be surprised to see a lot ruin of come out of China in coming years, which is why I have no intention of investing there anytime soon.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter