Yesterday I sent you an article written by my Wyatt Research Managing Editor Jon Lewis.

In it, he talks about four reasons why you should avoid stocks in September.

And while I’m certain that his points are completely valid, and exactly correct, that doesn’t mean that they’re beyond scrutiny.

I also believe that for most investors, though this information is certainly compelling and accurate, it’s ultimately not useful.

And as promised, there have already been some fireworks. Jon isn’t exactly pleased that I’m going to spend today kicking the tires and looking under the hood of his article.

But he’s a big boy, and he probably won’t get his feelings too hurt if I take issue with his article’s conclusion – namely that you shouldn’t buy stocks next month. Just in case, if you don’t hear from me anymore after this article, you’ll know why…

To recap, Jon states you should avoid stocks in September for four reasons:

- Seasonality is against you. September is historically a weak month for equities.

- The upcoming presidential election creates uncertainty. People aren’t likely to sustain the current rally with the election hanging over their heads.

- Both the S&P 500 and the Dow are butting up against technical resistance.

- Volatility is rising off of extreme lows, and stocks usually move opposite volatility.

First off, I have to reiterate – I agree with all of Jon’s points. But all of these points are macro events. Macro just means big, basically. And contrary to what most investors believe, macro events rarely impact micro actors in a significant way.

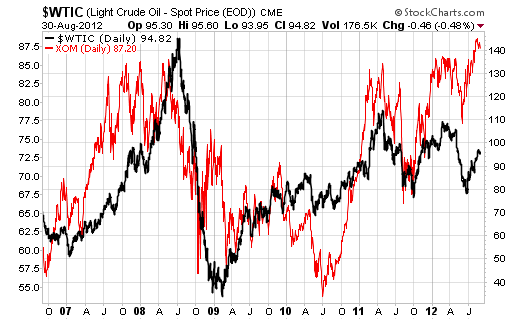

The biggest example of a macro event that people put way too much thought into for their individual investments was the huge oil price movement in the summer of 2008.

As soon as oil prices started to rise, people couldn’t buy individual oil companies fast enough. It was a completely logical thought process: oil prices are going up, so oil companies must be rolling in the dough – therefore I’ll buy Exxon-Mobil (NYSE: XOM) since it’s the biggest oil company in the world.

Unfortunately, this completely logical thought process had almost nothing to do with the success or failure of individual oil companies.

For an oil company, the price of oil is just one data point among thousands that impact the bottom line. It’s definitely important, but a company like Exxon does not succeed or fail depending on oil’s price swings. Even big price swings!

I’d even argue that the price of oil is a terrible indicator if you want to buy a company like Exxon at the right time:

If you bought when oil was on the rise in 2008, it was one of the worst times to buy Exxon. And if you bought when oil was at its cheapest in 2009, it was one of the best times to buy Exxon.

I wouldn’t suggest looking at oil prices at all when you’re deciding to buy Exxon or not. That’s because Exxon is either a good company to own at a certain stock price because it’s a good business, or not. It’s not like people are going to stop using oil anytime soon, nor is it likely that people will start using a lot more oil anytime soon.

Paying attention to even a yearly oil price chart won’t give you anything approaching an accurate idea of what’s happening to Exxon – let alone daily, weekly or monthly. And yet, that’s exactly what millions of investors did in 2008. They bought Exxon when oil was near its highs in 2008, and then a bunch of them sold when oil dropped in 2009.

My point is: successful investors rarely (if ever) consider macro events when it comes to individual investments.

And the kind of business you want to own for the long term is exactly the type of business that can succeed regardless of who gets elected, or whether the broad market is up against technical resistance – or even whether its main product fluctuates wildly in price over a one-year period.

I feel a bit sheepish writing these words to you today, because I’m sure it wouldn’t be tough to find dozens of examples where I ignored this rule of investing. It’s really, really difficult to ignore the big picture when you’re investing.

But if you want to succeed as an investor, you have to.

I’m sure Jon would agree.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter