If someone were to predict that a public company with a $382-billion market cap would see that market cap rise nearly 50% to $572 billion in less than three months, I would view that someone with rightful skepticism. It’s difficult enough for the fastest-growing small fry to move the needle so far in that short a time (excluding a takeover, of course), much less a behemoth of such girth.

That’s exactly what Apple Inc. (NASDAQ: AAPL) has done, though. Its shares began 2012 trading at $409. They closed Wednesday’s trade at $617. Apple is truly endowed with the Midas touch, or should I say the "i" touch, because it seems everything with an "i" in front it – iPad, iPhone, iPod – turns to consumer gold.

There is more to Apple’s price appreciation than irresistible electronics. Speculation on what Apple was likely to do with its $97.6-billion cash horde – idling in money market instruments and short-term and long-term marketable securities – contributed to the share price run-up.

On March 19, the speculation was settled when management revealed plans to initiate a dividend and share repurchase program beginning later this year. Specifically, Apple will pay a quarterly dividend of $2.65 per share starting in the fourth quarter of its fiscal year 2012, which begins July 1. In fiscal year 2013 – beginning this October – it will also commence a $10-billion share buyback.

I thought the market’s reaction to the dividend and buyback news was interesting. There is an axiom that implores investors "to buy the rumor and sell the news." Investors bought the news instead. Apple shares are up nearly 5% since it announced its dividend commitment.

I can’t say I’m surprised. This isn’t the go-go 1990s when investors had blind faith in management’s ability to reinvest profits in high-return projects. More investors today realize – and we’ve seen this in High Yield Wealth – that their cash flow matters as much as cash flowing to the company. They view dividends as a sign of strength, not weakness.

It’s a message I think Warren Buffett might be warming to. Buffett has long argued that the best use of Berkshire Hathaway’s (NYSE: BRK.a) cash was for him to reinvest it instead of returning it to shareholders.

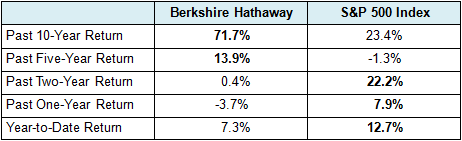

He’s got a point: Berkshire Hathaway shares have appreciated more than 1,600% since 1990, far outpacing the S&P 500 Index, which is up 290% over the same time.

But Buffett’s point becomes less convincing when you look at more contemporary data. The larger Berkshire has become, the less it’s been able to outpace the S&P 500 by such a yawning margin. In recent years, Berkshire has actually been outpaced by the S&P 500.

Investing is a what-have-you-done-for-me-lately business, so I’m not surprised that Buffett has moved on formerly immovable issues that a few years ago would have been unfathomable. Most notably, Berkshire split its secondary "B" class of stock in 2010. In 2011, it announced a share repurchase plan.

An openness to share repurchases is an encouraging sign Buffett might be amenable to a dividend. In the past, Buffett has been critical of share buybacks, stating in his 1999 letter to shareholders that they can be an "ignoble reason: to pump or support the stock price."

Who’s to say what’s ignoble and what’s noble these days?

There are a few other reasons I see Buffett backing away from his aversion to paying dividends. Like Apple, Berkshire has the enviable problem of too much cash, more than $37 billion of it.

Recent big acquisitions to Berkshire’s portfolio of companies haven’t moved the needle. It appears that multi-billion dollar purchases of Burlington Northern and Lubrizol don’t make that much a difference when the entire enterprise’s value exceeds $200 billion.

Any acquisition below $10 billion really is insignificant when the forest (Berkshire) has expanded with the addition of so many trees (acquisitions) in the recent decade. Worthwhile $10-billion acquisitions are few and far between, and even acquisitions of that magnitude can get lost in the forest.

A dividend is the theoretically correct move when the money can’t be put to higher-value use. Investments, after all, are valued on present value of future cash flows; that includes cash flows to investors. Over the past 45 years, Berkshire shareholders have received no cash from the company. They could only monetize their investment by borrowing against it or selling it. The time is near for many investors to monetize their investment.

It’s not like Berkshire would be punished for implementing a dividend either. Apple, Oracle (NASDAQ: ORCL), Cisco Systems (NASDAQ: CSCO), and Microsoft (NASDAQ: MSFT) have all removed the stigma of paying dividends. Paying a dividend no longer signals the end of growth. Companies can grow and pay a dividend. And investors will reward them.

Warren Buffett loves the dividends Berkshire Hathaway receives from its investment companies. More investors would love Berkshire if they were to receive dividends from it. A dividend – as Apple investors know – is one strategy to get the share price moving higher. Perhaps that’s the best option to get Berkshire’s share price moving higher, too.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter